While most reviews and commentary from the media on last week’s all-star GRAMMY® salute to Stevie Wonder has largely focused on Beyoncé’s “redemptive” performance, after her “Precious Lord” GRAMMY® gaffe which was largely viewed as a grand misstep and dis to R&B songstress Ledisi, who performed the song during her role as Mahalia Jackson in the movie Selma, there were far greater moments to ponder. And most of them had nothing to do with music. From slavery, to Nixon, to black pride on primetime television, Stevie Wonder: Songs In The Key Of Life – An All-Star GRAMMY® Salute, was a history lesson, and ironically, possibly the best Black History Month programming I’ve seen on television all of February.

Much like Prince, who snuck in a Black Lives Matter reference at the GRAMMYS®, or D’Angelo’s socially-charged SNL performance, the Stevie Wonder tribute, which aired about a week after the GRAMMY®, was full of under-the-radar references which speak to black culture: its essentiality, its influence and its beauty.

From the opening of the program, black folk were here to let America know we are dealing with royalty in saluting the 25-time GRAMMY® winner. Host LL Cool J asserted, “If you make music in any way, you learned something from Stevie Wonder.” A slightly awkward pause was followed up by a flurry of applause, perhaps the majority of the audience discovering this truth for the first time. The hip hop legend, actor and recurring GRAMMY® host went on to reminisce on a personal note about how his mother’s incessant spinning of “Living For the City,” from Wonder’s 1973 album Innervisions, taught him about the streets. LL, who hails from Hollis, Queens, New York City, would – like all young black men – need to learn how to Survive While Black, especially in a city with one of the most justly criticized police departments in the nation.

The song, which focuses on economic injustice and its repercussions for blacks is raw and jarring and brilliantly sequenced on the album. After all, just before it, we hear an ethereal and hypnotizing “Visions,” which although political in its own right, is aesthetically 180° from what we hear next. “Living For the City’s” musical production is eerie and anticipatory, with Wonder’s vocals assertive and damning. When Wonder illustrates an innocent and somewhat naïve black man being thrown in prison and slapped with a ten year sentence moments after his arrival to New York City, it sends shutters through the listener.

“Get in that cell, nigger,” says an officer as you hear the metal bars shut behind the brother from “Hard-time Mississippi”. The lessons LL was referencing speak to the daunting and relentless tasks young black men must master to avoid such an encounter at all costs. His referencing of the song also reminds us of Wonder’s perpetual pulse on the brutality against black people, which has a particularly potent redolence as we find ourselves currently in a cycle of protest and uprising against racially charged stopping, frisking, choking, beating and murdering.

Actress and comedienne Maya Rudolph touchingly reminisced about her late mother, Minnie Riperton, and the relationship she shared with Wonder, which she described as one with her “friend and musical soul mate.” To hear Riperton’s name on primetime television in 2015 was a victory within itself. An unsung musical genius, Riperton’s range – both vocally and artistically – should not go unnoticed or under-appreciated. Rudolph then described Wonder’s tour de force, Songs in the Key of Life, as “the greatest album of all time,” before welcoming Lady Gaga to the stage.

Gaga’s ode to Wonder was heartwarming for sure, particularly her personal confession that his album was the first she had ever put into a CD player on her own at six years old. (Speaking of which, am I the only person who had their first I Feel Old Moment when she said “CD player”?) However, the choice/assignment of song was off the mark. “I Wish,” a song which muses on the innocence of childhood, is so culturally nuanced that it felt inappropriate for the well-meaning Gaga. Watching and listening to her sing the words, “Looking back on when I was a little nappy-headed boy” was just… weird. (But it’s worth noting, Gaga has steadily gained my respect as an artist. My ears initially perked up this past fall when I heard her sing a rendition of Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life”, during her PBS special with the masterful Tony Bennett. And although in protest, I did not watch the Oscars, I later watched Gaga smash that Sound of Music tribute.)

Almost as curious was country music group The Band Perry, singing “You Haven’t Done Nothin’”: a song with a blistering message to then-President Richard Nixon, from Wonder’s 1974 Fulfillingness’ First Finale. But seeing as Nixon was a fucktard universal in his bigotry, it really doesn’t matter who serenaded this political gem. What was perfect about this selection was that it was performed at all, and that the inspiration for the song was made plain. Media mogul Tyler Perry described it as “one of his funkiest and most political,” before introducing the country band of siblings as, “three members of my extended family…The Band Perry,” which was an obvious tongue-in-cheek acknowledgment of violent origins of surnames as it pertains to African Americans.

I was particularly touched by the tribute from India.Arie, Janelle Monáe and Jill Scott. Singing one of Wonder’s most beloved classics, “As”, their reverence, awe and utter nervousness was palpable, and that was a good thing. For a black girl like myself, who grew up sitting on the floor playing Wonder’s music on vinyl and levitating to musical euphoria every time, I appreciated the humility and almost girlish charm these women had as they sang to their idol. Those memories are attached to the cultural experience of growing up at that time. I knew a “Village Ghetto Land,” and witnessed elements of its poignant lyrics first hand. My grandmother entered the room of her surprise 60th birthday party to “Isn’t She Lovely.” Too many times to count, I sat in my den and ran my fingers across the braille on Talking Book in amazement, and had a spiritual connection with “Golden Lady” on a road trip in the back of my sister’s car as the sun pierced through the window. This music was my life, and it was the life of all of black America, uniquely inextricable from our most foundational molding. I felt the spirit of that in their performance. From their unison stab at the classic “Al-Waaaayyy-aye-Ee-Yay-Aye-EE-YAY-a-YEE-Yay” riff that leads into the Rhodes (originally played by Herbie Hancock) solo and vamp, to Scott’s knowing spirit as she lovingly and timidly growled, “We all know…” their performance put me in the mindset of the wonder of Wonder, who, as Tony Bennett so elucidated, is often admired for being an entertainer but often under appreciated for the unending layers of his artistry. Although I am a self-proclaimed Stevie aficionado and a production geek, before this performance, I had never seen the elements of my sheer delight toward Stevie encapsulated on television. That part of me that would raise my shoulder to my ear and make me cover my mouth at his presence because it’s FRIGGIN’ STEVIE WONDER.

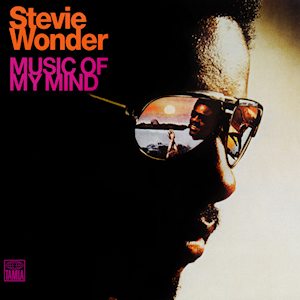

Other noteworthy moments include the introduction of British superstar Ed Sheeran’s second performance, which referenced that his “Using the technology of the day…” builds upon the foundation that Stevie Wonder laid with albums like Music of My Mind, where Wonder played most all of the instruments himself. In these times, where seeing a black artist hold and play an instrument on primetime television is akin to seeing Bigfoot, it was refreshing to have the masses be reminded that not only do we “play those things” but have a rich legacy of innovating instrumentally, with Stevie being no exception. To that end, it would be remiss of me to not praise the beautiful arrangements and impeccable integrity kept throughout the various renditions of Wonder’s music, under the direction of the great Greg Phillinganes, a most appropriate position for the former Wonderlove member and one of the most important session players of the last forty years.

While the accolades poured on for Wonder throughout the two-hour tribute, it was Jaime Foxx – who has his own hosting credits from another Stevie Wonder tribute in 2002 and introduced Wonder to close out the show – who said it best… and funniest: “Stevie Wonder has more talent in his braids than most of the artists today. That’s why he’s been able to reign for decades.” Then, leaving nothing up for debate, asserted that Wonder is, “the most important figure in music of all time.”

As Wonder took to the stage, with his signature shirt and pants set – this time in all black with an adorning of gorgeous, clear stones – and his band tore into “Contusion” from Volume 1 of Songs in the Key of Life, Foxx’s proclamation was duly noted and it was clear that the king was in the building. Performing a medley of hits, ballads and party jams, Wonder elicited the gamut of emotions, with the camera capturing it in the faces of Gladys Knight, Tyler Perry, John Legend (who performed a beautiful rendition of the Wonder B-side, “I Believe When I Fall In Love It Will Be Forever”), and Janelle Monáe, who was completely overcome when Wonder played the opening chords to “You Are the Sunshine Of My Life”. Who else but Wonder could make a GRAMMY® tribute feel like a family reunion?

Closing his medley with the ever-popular choice of “Superstition” was classic and felt fitting. However, to my surprise and delight, the entire final segment was dedicated to Wonder’s essentiality in the movement to deem Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a national holiday. Cameos from Ambassador Andrew Young, Rep. John Conyers Jr., and singer and activist Tony Bennett captured an authentic understanding of Wonder’s use of art to, as LL Cool J noted in his introduction of the segment, “Once and for all” call out those – including then incoming president Ronald Reagan – who persistently pushed against the bill. “Once and for all” describes the inspiration for the opening lyrics of Wonder’s “Happy Birthday,” the movement’s anthem and single element that turned the tide on the matter, directing the nation’s laser focus on Congress.

You know it doesn’t make much sense

There ought to be a law against

Anyone who takes offense

At a day in your celebration

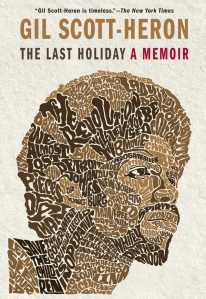

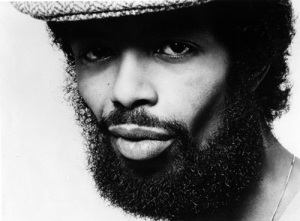

Wonder’s activism in his music and in physical action has been consistent for decades, with countless songs that have brought awareness to the plights of black people in America and Africa, and even in both using and sacrificing his prominence by being arrested for participating in peaceful protest. Gil Scott Heron brilliantly recounted this period in his posthumously released memoir, The Last Holiday, which focused on his time with Wonder as the opening act on the Hotter Than July tour from 1980-81, which was strategically paralleled with the MLK Day campaign. In Heron’s poem, titled “Dr. King,” he writes:

Wonder’s activism in his music and in physical action has been consistent for decades, with countless songs that have brought awareness to the plights of black people in America and Africa, and even in both using and sacrificing his prominence by being arrested for participating in peaceful protest. Gil Scott Heron brilliantly recounted this period in his posthumously released memoir, The Last Holiday, which focused on his time with Wonder as the opening act on the Hotter Than July tour from 1980-81, which was strategically paralleled with the MLK Day campaign. In Heron’s poem, titled “Dr. King,” he writes:

I admit that I had never given much thought

As to how much of a battle would have to be fought

To get most Americans to agree and then say

That there actually should be a Black holiday

But what a hell of a challenge, how far would Stevie go

To make them pass legislation tabled 10 years in a row?

Wonder, along with several civil rights activists, were relentless until the historic bill was passed on August 27, 1984. Dr. King would become only the second person in American history bestowed with a federal holiday.

In true Wonder fashion, he was gracious and full of gratitude for his honor last week, but swiftly turned his adoring fans’ attention to subjects away from himself, recognizing Dr. King’s infinite relevance and challenging artists to use their forces for good. “I encourage the songwriters . . . all of us as songwriters, to write songs about love, to inspire and encourage our family. And encourage our family as people in the media and press. Everywhere . . . to inspire . . . inspire this world . . . inspire this planet.”

The knee-jerk reaction for a black person to tell you they are “blessed,” “too blessed to be stressed,” and other affirmations rooted in religious culture, is a complex one that forces us to look at how our unique experiences as enslaved people has shaped the way Christianity is viewed even today and used as a life source for black folks. To see this part of the experience on network television outside of the context of faith-based programming was staggering.

Historically, Wonder has obviously not shied away from his Christian faith in his music, either. Songs like “Heaven Is 10 Zillion Light Years Away,” “As,” “Have a Talk With God,” “You Will Know,” “Evil,” “Jesus Children of America,” “The First Garden,” and “Ecclesiastes,” among many others, have directly and indirectly illustrated Wonder’s faith and he did not mince words during his tribute, while he had the attention of all of America. Quoting Matthew 18:20, Wonder added, “Because I believe that if we come together… as it is said, when two or more believe, then almighty God is between it. Let us come together. Let us fool everyone that thinks it’s impossible…let’s make the impossible so very possible by loving. Love is the key.” His charge to songwriters for a higher standard of themselves was like a silent boom in that theater that had to be respected, but should not have come as a surprise to anyone who knows anything about Wonder. (Remember his taking Lil Wayne to task over the rapper’s Emmett Till reference? Yeah.)

While reverence for The Eighth Wonder of the World, AKA Stevland Judkins Morris Hardaway, is universal because his message in life and in music is about humanity’s inhumanity to man, which we can all feel on various levels, I so appreciated how his folks, in particular, lifted Wonder to such deserved heights in a way so idiosyncratic and enriching. It makes me excited for whoever’s ears were truly opened before Stevie spoke, and what their pen may now be destined to say.

To echo Jamie Foxx, “The Academy…thank you.”