Rest in peace to the GREAT Gil Noble. A last name such as yours could not be more befitting. A great debt is owed you from not only the Black community, but the world. What would journalism be without you?

================================

Originally posted October, 2011

After 43 years on the air, last Sunday, ABC’s Like It Is came to a sudden and saddening end. Emmy award winning producer and host Gil Noble suffered a stroke this past July, and the fate of the program had been subsequently undetermined. The last episode, which re-aired yesterday, was hosted by ABC newscaster Lori Stokes and featured Noble’s daughter Lisa, Danny Glover, Al Sharpton, journalists Bill McCreary and Les Payne, and New York City Councilman Charles Barron, who praised Noble’s maverick style of journalism, having profiled political prisoners like Assata Shakur and Mumia Abu Jamal.

Noble, who has interviewed some of the most prolific figures in American history, from Adam Clayton Powell, to Muhammad Ali, to Bob Marley, is known for being one of the most provocative journalists of our time. With Noble ultimately becoming unable to return to the public affairs program, ABC has created a replacement called Here and Now, which is receiving push back from the Black community for its seemingly half-hearted development.There is also concern that the new program, while promising to pay particular interest to topics relevant to the Black community, will not be in the same raw spirit, which is Noble’s legacy. If that’s to be so, it’s a real shame. There has been no other program that has given voice to the totality of Black America — politics, current and public affairs, arts, culture and more — than Like It Is. Further, I can’t think of a journalist more progressive, introspective, and passionate than Gil Noble. He was also the first image of a Black journalist that I had ever seen, which made an indelible impression on my conscious and subconscious young mind. Growing up watching Like It Is every week was as routine as afternoon football, church, or any other traditional Sunday activity. Being part of a household which nurtured both the arts, and social and cultural awareness, Like It Is was a reflection of my real life lessons and experiences, particularly as it pertained to jazz.

Noble, an accomplished pianist who initially pursued a career in music, is an avid jazz enthusiast. He has been on Jazz Foundation of America’s Board of Directors for many years, and he frequently showcased musicians on his program. Unlike the comically short and non-comprehensive interview segments that are so typical when it comes to jazz profiles on television, Noble would dedicate his entire program to the likes of Oscar Peterson, Sarah Vaughan, Dizzy Gillespie, Abbey Lincoln, Dr. Billy Taylor, Lena Horne, Max Roach, Carmen McRae, Erroll Garner, and Wynton Marsalis. His narratives, in-depth and introspective, helped develop my broad view of how jazz musicians could be perceived. Noble presented jazz in journalism from a vantage unlike anyone else. He was not only a student and devotee of the music but a strong advocate for passing the traditions on to the next generations.

During his interview with Sarah Vaughan, she took him on a tour of her Newark, New Jersey home town, which included a stop by her elementary school. The children playing in the school yard of the building gravitate toward the cameras, and chat it up with the host and his iconic interviewee. As they begin to walk away, Noble stops in his tracks and addresses the students through the school’s gate. “Do you know who this lady is?” he asks. He then responds to the rounds of flat “Nos.”

“That’s part of the problem, isn’t it?” Noble’s blunt yet eloquent scrutiny was his signature. As he walks away he underscores, “If you don’t know who she is, when you go back to class, ask your music teacher who she is, and why she never told you about her.” It was not until adulthood that I realized how immensely crucial and precious this program was for that one example alone. That the likes of this type of education was reaching a network television audience every week remains monumental. So you can understand my elation to make his acquaintance about five years ago.

When trumpeter Charles Tolliver was preparing to release his big band album, With Love, he had a distinct vision for his project, down to the liner notes, which he implored Noble to write. Tolliver, who got his professional start through his friend and mentor, saxophonist Jackie McLean, wanted to pay homage in a personal way. Noble grew up with McLean in the Sugar Hill section of Harlem and they were best friends from childhood until McLean’s passing. Tolliver thought it would be most fitting and honorable if Noble would pen the notes for his Blue Note debut (which he did, beautifully).

Working on this album with Tolliver, I remember that blustery day, trekking up to ABC in the Lincoln Center vicinity to talk details with Mr. Noble and Mr. Tolliver. There were full circle moments to go around that day, for both Tolliver and myself. For me, meeting the man who inspired my perspective about jazz coverage in mainstream media would prove life-changing.

We sat in a waiting area before being ushered into Noble’s office. We waited about ten minutes for him to join us, during which time I timidly perused his immense library of books. The room was adorned with African artifacts, artwork and posters, including the famed photo of 52nd Street nightlife in New York City, which was the hub for bebop in the 1940s. When he entered the room, my stomach dropped. He is a tall man, but his presence was ten times that of his height. His demeanor is intensely quiet, similar to his on-air persona. He sat disarmingly relaxed behind his desk, and Tolliver and I opened the conversation.

We sat in a waiting area before being ushered into Noble’s office. We waited about ten minutes for him to join us, during which time I timidly perused his immense library of books. The room was adorned with African artifacts, artwork and posters, including the famed photo of 52nd Street nightlife in New York City, which was the hub for bebop in the 1940s. When he entered the room, my stomach dropped. He is a tall man, but his presence was ten times that of his height. His demeanor is intensely quiet, similar to his on-air persona. He sat disarmingly relaxed behind his desk, and Tolliver and I opened the conversation.

We talked about music in a general way, about Tolliver’s project, but mostly about Jackie McCLean. J-Mac, as he was nicknamed, had just passed away and I could see the sadness in Noble’s eyes as he spoke of him. The loss of his best friend was obviously hard and the vacancy in Noble’s heart was transparent. Noble talked about their childhood, their adventures together as teenagers, and he spoke specifically about the way drugs plagued the lives and careers of so many jazz musicians and how McLean, who suffered from and conquered drug addiction, educated him about the music industry as it related to the fragility of growing up Black in that era. It was a conversation that I will never, ever, ever forget. Getting a one-on-one education from Noble, in the presence of a jazz master in Charles Tolliver, discussing a giant in Jackie McLean was a beautiful and crucial experience. The climate of mainstream jazz journalism (and especially criticism) today is not only broadly monochromatic and misguidedly audacious, as usual, but technological advances give voice to virtually anyone who feels like being an authority on the subject, which isn’t always a good thing. (Examples: Writers who haven’t lived as many years as some artists have had professional careers making proclamations about who is and isn’t innovative, or telling off the Black community of jazz musicians, blaming them for why they are being left out of critical dialogues.)

[Insert deep breath]

Additionally, writers seem to be writing for other writers, rather than using their platforms to work in tandem with the music and nurture a community at large which — fathom this — actually gives a damn. The dangerous duo of ego and lack of diversity remains the affliction that keeps journalism in jazz from reaching full potential. Too many of these journalists have traditionally put themselves in front of the artists, and ahead of the music. Moreover, there is still a severe lack of proportion when it comes to editorial and coverage of African American jazz musicians.

What watching Gil Noble all of these years, and having that candid and personal conversation with him has taught me is infinite. But in more specific terms, what it taught me is that as a writer, especially a writer of color, I have to be passionate about truth.

Tim Soter/WireImage

The beauty of being a writer, or of performing any artistic expression, is freedom. It is truly liberating. But as a Black person writing about a Black art form, which is mainly analyzed, critiqued and examined through the scope of white men, I have a duty beyond being poetic or inciting. There is another level of responsibility, and here is the essence of Noble’s genius. His depictions of artists were always supported with a social contextualization — let’s go back to his doubling-back to those students with that message about Sarah Vaughan. Jazz is one art form that cannot be written about it a bubble, because it is distinctively intertwined with a culture. Why this is a concept that is resisted and resented in journalism is bewildering to me.

But thank goodness for Gil Noble. He is my hero. Acutely informed with an immense amount of integrity and creativity, he has laid the groundwork that I can only hope to aspire to build upon. His passion for jazz, politics, and the scope of the African diaspora; and his ability to create a television program which successfully married these subjects for all audiences for decades, is most inspiring. Most importantly, his convictions spoke through his journalism. He didn’t have to spend time identifying who he is to his audience…it’s eloquently obvious in everything he produced. That’s class.

It is my hope that Like It Is will remain on the air somehow (perhaps through syndication, a-hem, a-hem, BET and TVOne, step up). Most importantly, I hope his wish for the program’s archives to be utilized in educational spaces comes to fruition. It is an unparalleled resource.

Like It Is debuted just two months after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and was largely inspired by this event. The last broadcast of Like It Is aired on the same day as Dr. King’s memorial dedication.

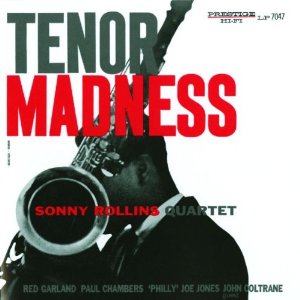

It was my mother who was the first woman jazz enthusiast I knew, which was probably the single most impactful part of her persona on my life. She could scat, and she could sing, and she is the funniest mimicker of some of jazz music’s rarest personalities. She is also a great debater. She and my step-dad would have a never-ending argument over who “won the battle” between Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane on “Tenor Madness”. She voted Trane, and would quote the various aspects of nastiness in his solo to make her case. (She loves Sonny too, just for the record.)

It was my mother who was the first woman jazz enthusiast I knew, which was probably the single most impactful part of her persona on my life. She could scat, and she could sing, and she is the funniest mimicker of some of jazz music’s rarest personalities. She is also a great debater. She and my step-dad would have a never-ending argument over who “won the battle” between Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane on “Tenor Madness”. She voted Trane, and would quote the various aspects of nastiness in his solo to make her case. (She loves Sonny too, just for the record.) . We were steeped in our African-American heritage in a way that many of our peers were not. My mom always let us know that this was music that we should be proud of, not by making some big jazz history speech, but by the sheer joy it brought her. It was completely infectious. I immediately loved this music, and she nurtured that love. I’m certain that the gift of passing down this tradition is what made me want to pursue a career in jazz, which was always cool with her. Starting out in this industry meant paying a lot of dues (which included sometimes earning little money) but the sacrifice never concerned her. She was down for the cause, and I will always be grateful to her for that. And for the music.

. We were steeped in our African-American heritage in a way that many of our peers were not. My mom always let us know that this was music that we should be proud of, not by making some big jazz history speech, but by the sheer joy it brought her. It was completely infectious. I immediately loved this music, and she nurtured that love. I’m certain that the gift of passing down this tradition is what made me want to pursue a career in jazz, which was always cool with her. Starting out in this industry meant paying a lot of dues (which included sometimes earning little money) but the sacrifice never concerned her. She was down for the cause, and I will always be grateful to her for that. And for the music.